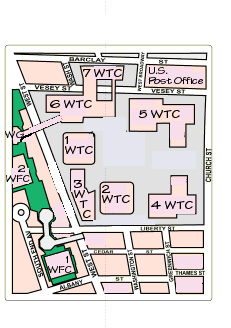

1 WTC: North Tower

2 WTC: South Tower

3 WTC: Vista Hotel

4 WTC: Southeast Plaza Bldg:

Commodities Exchange

5 WTC: Northeast Plaza Building

6 WTC: U.S. Custom House

7 WTC: Tishman Center

1 WFC: Dow Jones

2 WFC: Merrill Lynch

3 WFC: American Express

(north of Winter Garden)

Circumnavigating the frozen zoneFive fortnights walking the perimeter

Friday, 26 October: Rising above the quaint low rooftops that form the view from the window behind my monitor, this morning the very long black arm of a crane doing some local job reaches skyward, American flag flying high. W. doesn't have anthrax and neither do I. A Nassau County cop on duty on Hudson across the street from my bank tells me there are no dumb questions, so I ask why Varick and Hudson are open but Houston and King streets are blocked bigtime around the federal building that occupies the entire block--the building that houses my branch post office. He says that the I.N.S. entrances are on the side streets. Oh! ... I choose not to pursue this with him, but I do believe that that building is where some suspects rounded up right after the attack are still "detained." I'm not making that up. And after dark it's lighted up like a baseball park. I haven't received any mail in days. The crowds are long gone from West Street, but I understand that a small crew have made it their 24/7 job to stand watch, waving Thank You signs, at what's come to be known as Point Thank You, West and Christopher streets, and that recovery workers are grateful for the gesture. Hat's off, folks. But I'll go up there another day. Now I turn south on West, staying on the city side. Brilliant sunlight bounces off whitecaps in the river; I'm not overdressed in a goosedown parka. Votive candles and messages still adorn the chintzy strip of sidewalk at the end of Canal Street that the City assigned the foreign press for the couple of days when the frozen zone was solid south of Canal. No voting blocs among their readers. A crane loads debris onto barges at Pier 25. I pass one other pedestrian on this side between Houston and Harrison streets. Although the frozen zone has shrunk again, at Harrison a cop directs me eastward, and I again pass the point on Greenwich Street where I reversed my rush southward that punchdrunk Tuesday morning.  The north boundary of the frozen zone now is staggered

and green mesh fixed to the chainlink deliberately blocks

the street-level view. The City announced weeks ago that

the boundary would drop to Park Place. Now that actually

has happened along part of the northern stairstep.

The north boundary of the frozen zone now is staggered

and green mesh fixed to the chainlink deliberately blocks

the street-level view. The City announced weeks ago that

the boundary would drop to Park Place. Now that actually

has happened along part of the northern stairstep.

The mood varies from checkpoint to checkpoint. I'm momentarily startled to hear cops joking loudly with each other at Greenwich and Chambers. A high school and community college are nearby and the cops must feel less stressed out now that Greenwich south of Chambers is open. I've happened to witness a few chance encounters lately between recovery workers some distance from ground zero. They hug like best friends who haven't seen each other for years and the cheerful camaraderie suggests enduring bonds. The farther south and east one walks along the northern perimeter, the more the mood is the same solemnity of a month ago. At West Broadway, the uniformed presence is very alert to cameras and quick with the "This is a crime scene" baloney. Like shooting a photo from two blocks away is going to disturb evidence?

|

![[photo]](gx/_wtcs_wb.jpg)

photo: Terry Schmidt

Church Street southward from Warren Street,

11 September: Weber's at right. |

Weber's has a closed sign on the door, and inside

merchandise is numbered in lots--an I-told-you-so

that gives me no pleasure. A lot of people besides

me will miss that closeout store. The Odd-Job store

a half-block up Cortlandt from ground zero won't be

reopening soon either, but other Odd-Job stores show

no sign the Weber's competitor has taken a fatal hit.

<updates, 28 November

and 30 May>

This is the first time I've been glad that Computer Book Works, which was across Church Street from Weber's and a few doors west on Warren, lost its lease and moved up to Reade Street several months ago. <photo update, 18 July 2002> And here at the intersection of Church and Barclay streets: historic St. Peter's Church, where firefighters laid the body of Mychal Judge, the NYFD chaplain who was killed while giving a fireman last rites <clarification, 30 May 2002>. |

|

A block south is the corner of Vesey where last

week I stood alone and shaken, then 5WTC,

beyond the hidden pile the torn-up 4WTC wreckage.

5WTC looms stark, dark, disturbing. The site will

be prepared tomorrow to close down for a memorial

service Sunday afternoon for victims' families

in Church Street in front of 5WTC. Oy. I dunno. ...

I'm relieved to turn away from this particular

ruin and to see through a window near Broadway

the shoe repair guy's familiar smile.

I walk a couple of blocks down Broadway on the west side, open for the first time below Vesey. Murals have been removed from the Vesey Street side of St. Paul's Chapel's wrought iron fence and for the first time I read the messages on Broadway. Church officials have hung canvas on that fence with markers for new messages and I watch a man with a backpack write sadly that his family helped build the WTC. In the next block, a notice to police, a few weeks old, lists dangerous buildings. Among those that can't be entered under any circumstances, in addition to the obvious, are 130 Liberty (the Banker's Trust building draped with black steel curtain, across Liberty from 4WTC), 90 West Street (that's between Cedar and Albany), 130 Cedar, and 30 West Broadway. Those that can be entered with an escort are the South Bridge (between stairs in a kiosk on the south side of Liberty and the WFC), 1 to 3 WFC, 140 West Street, and 22 Cortlandt (the Millenium [sic] Hotel). Crossed off the restricted list and added to the no-entry list: the Winter Garden. The air in J&R on Monday was if anything more contaminated than that in the streets; today big air purifiers are placed strategically throughout the outlets and do their job well. Customers are plentiful; hope they're buying. (A few days after 11 September word was about that you couldn't find a new notebook in all New York City. I found out it was no rumor two weeks after the attack in a chain electronics store on Union Square: On the counter where tethered cages let shoppers test laptop keyboards and see the screens were only empty tethered cages.) My last stop is Computer Book Works. I'm the only customer, but unlike Weber's at least CBW still is doing business. Try though I may, since this began I haven't been able to wrap my mind around anything having to do with software. Slashdot and the Register and XP stuff look way beyond meaningless to me. I leave CBW empty-handed and feeling guilty. As I walk across Chambers Street it's dark and I realize that I no longer stick close to the perimeter and no longer stop at every intersection where I can see the site. I've spent hours staring down those streets. I finally am becoming desensitized. I don't know whether that's a good or a bad thing. In my absorption with the West Village firehouses, I hadn't even thought about how close my precinct is to ground zero till the Daily News a few days ago began listing a funeral service on Staten Island Saturday for a Sixth Precinct officer. Now I'm going after the rest of the bad news. I swing up to West 10th Street. The last time I was here, a few years ago, the occasion was paperwork related to an apartment (not mine) burglary in progress that the Sixth foiled after I called 911. A squad car, lights flashing, now blocks through vehicular traffic at the corner of Hudson. I wonder if that has become standard. In front of the stationhouse, if the shrine is more modest than the one at the Sixth Avenue firehouse, feelings are as deep. On a pillar over to the right is a MISSING notice for the officer, the standard heart-breaking smiling photo. He was here. Now he's not. He could have been one of the cops who caught that burglar in a foot chase a few blocks south on Hudson. A sign in the foliage and messages in the raised planter:

I wrote a few weeks ago that I knew nobody in any affected building, not even friends of friends. That wasn't entirely true. It turns out that 20 men who didn't know me but who were part of my life perished. As Larry Groce said, we'll never take anything for granted again. At the eastern end of the Sixth's block of 10th Street, at Bleecker, is a gift shop. All the merchandise is imported from Afghanistan. In the window hangs an American flag. The firehouse--the one in the same block as Ed's apartment--is a couple of blocks east. Sunday, 28 October: The recovery operation and the city's mood have been blessed since 11 September with unusually dry and sometimes unseasonably warm weather. Today is no exception--another blue sky but with a crisp north wind. I stay away from the frozen zone on weekends, and especially would have today because of the memorial service for victims' families. But Dick calls early, wants to see ground zero, and must return to D.C. at 12.30. We view it from the north, east, and south, and I hope he'll write something about his first impressions. I don't notice the chemical stench anymore except where it's strong. He detects it as soon as we encounter a trace--upwind. The banner hanging from the building next to the Sixth Avenue firehouse has come untethered at the bottom; messages on the walls downtown too were showing wear and tear and most now are gone except in front of St. Paul's. Dick asks about something I've been seeing from the start but that hadn't registered consciously: What are all the nitrogen tanks for? (The oxygen tanks raise no questions.) He's the scientist around here, so I say, I dunno, what is nitrogen usually used for? Nothing he can think of that would relate to the recovery operation. <clarification, 9 June 2002> South of the site, Guard troops have vanished, leaving behind handwritten warnings everywhere not to photograph anything. Everywhere, people are photographing everything. As we walk up Broadway, another truckload of nitrogen and oxygen tanks rolls southward. Dick never saw a bookstore he didn't want to browse, and we drop into Computer Book Works where I buy a remaindered emacs book I probably could have copped cheaper from a street vendor. Hope that helps. Dick spots a guy in an SUV driver's seat, respirator clamped to his face, flag wrapped around his head, dog on the passenger side. Looks to me like a recovery volunteer, but I wonder what he's doing here today. This is supposed to be the first day of rest at ground zero since 11 September. Anthrax anxiety is running high in D.C., the atmosphere in NYC is noticeably different, Dick observes. I don't doubt that anthrax anxiety is--legitimately--high in media circles and among Post Office workers here and in Jersey, and maybe it is other places in the city and 'burbs, but it surely is not widespread downtown. I'm gravely concerned about the city's economic prospects and what this U.S. administration with its weird wind-up front man (I do not have anthrax. I can't say whether I'm taking antibiotics or have been vaccinated. I do not have anthrax) will do next at home and abroad (way too many Red Cross hits and civilian casualties). Nothing else. At brunchtime, restaurants in Tribeca and the Village are jammed, the mood indoors and out seems to be almost merry, and I wonder who BBC and some U.K. print media types talk to before reporting "New York City paralyzed by fear!" I think the street churn has a lot to do with the equanimity. As we leave the Greenwich Village Bistro, Dick learns that what he mistook for a bumblebee is in fact a gila monster. The black and yellow-clad little girl and her parents may be on their way to the Brooklyn Botanical Garden's Halloween party. Where we stand is on the route of the Village Halloween parade. Leading the march next week will be a phoenix, quite reflective of the local mood rather than an attempt to inspire a turnaround. At ground zero, smoke still rises from the fires, and as Dick leaves for home families are gathering for a memorial service where many will be presented urns of commemorative earth and ash from the pile, absent identifiable remains. Monday, 29 October 2001: What's wrong with this sentence: "[On 26 October,] I walked past Trinity Church, ghostly in its coating of dust, its wall covered with flowers and posters with condolences from mourners who have trekked from London and Bali and Tel Aviv"? ... The church that looked that way that day was St. Paul's Chapel (if you choose not to quibble with calling a wrought iron fence a "wall"). San Francisco editor David Talbot can be excused for writing that in a piece dated today in Salon. A lot of New Yorkers don't know what Trinity Church looks like either. (It too has a wrought iron fence, not a wall, in front.) On no day did Trinity look like Talbot's description. He got a few other details wrong too, but never mind. Few New York journalists get downtown right. <photos: St. Paul's and Trinity, 2 June 2002> Wednesday, 31 October 2001: The East Side matron who hoarded $7000 worth of anthrax medication must feel vindicated. The East 64th Street hospital stockroom clerk, a Bronx resident, who had the nation's first case of apparently non-media-, non-mail-related pulmonary anthrax died this morning. Al Qaeda was fingered instantly for the plane attacks; authorities seem to have no clue who's behind the anthrax terrorism. The NYPost blames Daily News publisher Mort Zuckerman--in jest, of course. Nobody else thinks the deaths--this is number four--are a laughing matter. If sleaze and insensitivity were illegal, News Corp. principals would be in jail. Friday, 2 November 2001: The suspect from San Diego who was just indicted was being held in NYC, and I wonder if he was in that I.N.S. jail down the street and was moved. The side streets now are open to traffic and, except for Jersey barriers still in the parking lanes, are pretty much back to normal. Broadcasts on all the usual VHF channels except 13--PBS--are again reaching downtown Manhattan; only my favorite FM station is still off the air, and probably will be till next year, I read in the Daily News. I still haven't cabled the equipment I bought to compensate. Something has dawned on me. The horror on the faces of onlookers in some photos isn't general. It's the expression of people seeing other people who've just chosen death by jumping over death by fire. I forget whether any are in "the show on Prince Street," as it's called here. Every time I visit, new images have been added. Some are shocking. Near the front of one of Here Is New York's two storefronts now is a photo of the partially burned press shields of one photojournalist, next to a shot of the program for his funeral service 19 September at a Village church. An unadorned video of ground zero in its first hours runs behind a curtain at the rear of the space. My timing has been lucky. There's never been a line when I've entered. More typically, as I left yesterday a line stretched halfway down the block. Today I visit a different pro/am exhibit, The September 11 Photo Project, on Wooster Street. Photographers have been encouraged to express themselves in words too, and for the most part that was a bad idea. The unbroken space is warehouse-huge, many of the prints are snapshot small, and that's a worse idea. The exhibit is worth visiting, but the show on Prince Street is mounted in a way that itself conveys the chaos of the events, larger prints crowded to dynamic effect in an intimate space. For good reason, that show has had a ton of publicity, and it's the one the pilot's wife from Las Vegas and her friends leaving 26 Wooster are looking for. I give them directions and cross Canal Street heading south. <photo, West Broadway at Canal, 22 May 2002> The retired couple from London sitting on the stools where Luisa from Chicago and I had sat in the cookie store on Broadway at Fulton had planned their trip before the attack and were undeterred. Flew to D.C., then Minneapolis, rented a car and drove 6000 miles, finally to San Francisco. He says U.S. airport security still is a joke; I tell him the House has just voted not to fix it. Although their bags were singled out for examination, he could easily have had a bomb packed in one that San Francisco airport security passed, he says. He's surprised and impressed by New Yorkers' resilience. "You taught us how," I answer. I'm thinking blitz. That was then. He thinks I mean Irish terrorists. I ask a cop on Broadway what the nitrogen is for. He thinks it powers the welders' torches. Also on Broadway, occasional clusters of firemen in dress uniforms, presumably after memorial services. Ever since WTC MISSING notices disappeared from the frozen zone new MISSING notices have been posted here and there for relatives who had nothing to do with the WTC. Next to the Brooks Brothers store at 1 Liberty Plaza a sign can be seen on the temporary structure above the green mesh'd chainlink fence: OCME DMORT/Field Mortuary. At West and Rector streets, the southwest extreme of the site, I draw a map of the WTC buildings for a young Italian who can't figure out which wreckage he's seeing. Beyond green mesh barriers on Greenwich Street north of Rector, glowing sparks shower from welders' torches. The welders stand on high platforms and shear overhangs from beams and girders sitting on flatbed trucks, usually one per truck, so they can be carried through the streets. Steam rises when the debris is hosed down at the mandatory vehicle wash. As the flatbeds pass the closest place civilians are allowed, steam still is rising from the massive twists of steel--a mobile exhibit of the most dramatic sculpures I ever expect to see. I don't have the poetry in my soul to describe them. One of the men standing next to me snaps one of these steaming girders with a digital camera. This is the first time I've wanted a virtual image of what I'm seeing enough to ask the photographer to email a jpeg. When he answers, "I don't speak English," we're at an impasse. I can't place the accent immediately and the man he's with hurries him away. I'd already decided to buy a camera and spend the rest of my life photographing NYC. Now I decide to buy a camera and spend the rest of the clean-up photographing this mournful parade <update: Job done? 30 May 2002>. (All wishful thinking--unless somebody wants to front $800 for the camera I crave and can't hope to buy. <update>) At Greenwich and Rector, a man is hefting two nitrogen tanks. I ask him what the nitrogen is for. The gas is forced into phone lines to keep water out, he says. Rector Street is torn up its entire length, giving an up-close and personal glimpse of NYC infrastructure. Phone lines? Probably several things. Lots of pipes in that trench. At the Broadway end a tall man in a tux is painting an announcement on raw plywood that his restaurant near Rector on Washington Street is open. Handwritten cardboard signs that say the same thing have replaced the National Guard's handwritten cardboard signs that warned against taking snapshots. The tall man in the tux has hung ads on Trinity Church's fence as well. The church is scheduled to hold its first services since 11 September Sunday. The vendor vultures who surfaced as soon after 11 September as they could obtain patriotic merchandise now sell NYFD and NYPD baseball caps and T-shirts too. The sidewalk in front of Trinity has become that neighborhood's counterpart to Canal Street. I restrain myself and don't ask one I've seen every day whether she also sells victim relics. At Cortlandt I stand on the west side of Broadway where civilians weren't allowed till recently, contemplating the way the wreckage has changed since the first time I looked past the damaged Odd-Job Trading and Century 21 stores. A man stops next to me and says in quiet wonder, "It's still smoking. ..." I've heard that again and again. Sometimes more, sometimes less, the fires still burn. Ralph tells me he was at work in his office on the 27th floor of the Century 21 office building when he heard the first plane, too loud, too low, then a massive explosion--the impact--followed quickly by a second explosion--fuel igniting inside the tower--explosions that had a quality unlike any explosion you've ever heard, Ralph says. He remembers it in slow motion. He and his co-workers rushed to the windows: a cloudburst of debris--ash, papers, larger, unidentifiable objects. Then they rushed to the elevators. While they were in the lobby debating which of the two exits might be safer, Dey Street or Cortlandt, the second plane struck. Till then people had been scared. Now they started screaming. Crouching, Ralph opened the Cortlandt Street door a crack. A storm of flaming fuel and debris was raining down from the south tower. They ran up Dey Street and, like so many that morning, Ralph headed for home on foot across the Brooklyn Bridge. When people suddenly started screaming he thought something had happened to the bridge. The south tower had collapsed. 4WTC was severed. This is the first time Ralph's returned to Manhattan. His office relocated temporarily to Brooklyn, and reopens Monday on William Street. He's here now because he didn't want to experience the first shock of this sight Monday morning. I feel so sorry for this gentle, wounded man. Ralph says that although the Century 21 building <photo, 2 June 2002> has been declared structurally sound and his business plans to move back there, people who've been in the basement have seen cracks in the foundation and he won't go back. For the first time I grasp why all those businesses want to relocate in midtown because of the trauma their employees suffered. I ask another cop on Broadway what the nitrogen is for. He thinks it powers the welders' torches. Take your pick--or none of the above. A volunteer from Philadelphia has been waiting since 11 September for this one-day opportunity to help. She invites passersby to write messages on the canvases hanging from St. Paul's fences, offers masks, and helps in whatever other ways she can. As I'm about to leave the zone, near the northwest extreme I turn the crude map of WTC buildings I drew at West and Rector upside down to try to explain to another perplexed Italian which wreckage she's seeing. She's flown here to run the marathon Sunday. Where are the towers, everyone wants to know. I'm still having a hard time myself distinguishing between 5WTC and parts of 4WTC. The last American I talk with today hails me by name--that's a first--from a hotdog stand in what I guess realtors now call Tribeca. Steve was the editor of a Manhattan weekly I once worked for briefly, then we often saw each other in passing when we worked for competing city government branches. Wearing a big Green for Mayor button, he's grabbing dinner to take back to campaign headquarters. The election--finally--is Tuesday. Barring unforeseen circumstances, of course. I learn on the 11 o'clock news that when NYFD survivor families and firefighters demonstrated at the site this morning against the City's sharp cut in the size of the uniformed force at the site, they had a dust-up with cops. Fists flew, firemen were arrested. One widow says she doesn't want her husband to become landfill. Oh, my. ... For want of something better to watch at 11.30 I turn to "Nightline." Arundhati Roy is a writer who has achieved quick, early critical and popular acclaim. I've been interested to read her, but hadn't yet. I hope that I'll come across something before too long that suggests she has acquired the maturity conspicuously absent from her public remarks about 11 September thus far, on ABC and in print. Till then, I won't be reading her after all. Roy seems to have the same ice water flowing in her veins as the Silicon Valley software entrepreneur who was complaining one week after the attack that wounds were healing too slowly; I wouldn't be able to keep that out of my mind while reading her. Consider the poignant cries in this paragraph from a piece written by Laleh Khalili for the Iranian--a writer and a 'zine I'd never heard of (link in Recommended Reading): How glibly Roy, to press her political point, dismisses the lives lost. The losses Ralph (who as it happens is black) and Khalili (who also lives in Brooklyn) suffered are nothing to Roy. She no doubt believes she has adequately answered the anguish of that Indian's How could they do such a thing; I don't want to think what her response would be to his pain that he can never bring his children back to their home next to ground zero."And I fear things I never had felt: I fear internment, and harassment at the airports, I fear the looks on the streets, and I feel grim and I feel dirty, and I feel guilty. Guilty! For what? For a bunch of zealots doing what I cannot contemplate, in revenge for some horribly inhuman treatment that is also beyond human comprehension? How do we ever rescue our dignity, fight for a cause, when so much devastation and havoc is wreaked by other people with whom you seemingly share this belief in the cause? And what to do for this wounded injured bloodied humanity that has lain to ruin in so many places in so many ways, by so many hands. ... And for what? And there is the grotesque celebrations in the West Bank. How can a suffering people feel no empathy?" Roy has positioned herself as the Jane Fonda of today's peace movement--glamorous, talented in her field, and a naive spoiled brat eager to trumpet her highly selective "compassion." --adpF

|

![[photo]](gx/_wtco_sr.jpg)