Thar she squirts

By Wolfgang Bechstein

PORT HACKING, New South Wales--Good old rubbery Gonbei (still to be admired nearby) has come a long way.

It has lounged away many a lazy afternoon on Inbanuma in Chiba, that sadly polluted lake surrounded by lush fields and meadows. (Yes, I spotted a kingfisher there once.) Gonbei has gone up Tokyo rivers, puttered through canals and locks, and checked out not a few harbor basins in its time. One highlight of its early life was boldly going across Tokyo bay and coming back in one piece, awed yet unharmed by mammoth tankers. It helped its chief mate and bottlewasher explore numerous nooks and crannies on the rocky Uchibou coast, and undertook occasional forays into the open Pacific on the Sotobou side of Chiba, once encountering a playful school of porpoises. It served as a platform for snorkeling the amazingly clear waters of Katsuura and around Ukishima.

Shipped to New South Wales

And some months ago, Gonbei was deflated, packed tightly into the corner of a container and shipped all the way to New South Wales. I personally wouldn't have minded just finding a good home for it in Japan and buying a new craft (or more likely a suitable second-hand one) here in Oz, but Reiko rightly surmised that our financial situation in the first year or so of our move would not easily suffer the purchase of more water toys, and therefore she urged me to bring Gonbei along. Given the fact that the bay on which we live now is a perfect playground for a light maneuverable dinghy with a shallow draft, I have not at all regretted following her advice.

It is "winter" over here now, but on sunny days the temperature can still creep close to 20 degrees during midday, and the sea is a moderate 17 to 18 degrees. I still occasionally go for a quick dip, especially when I'm wearing the short-sleeved wet suit that I use when enjoying my other water craft, a lemony yellow sit-on-top kayak. [The Celsius-challenged may consider those temperatures approximately 68, 63, and 65 degrees, respectively. --Ed.]

But winter, or more precisely the months of June and July, are also whale watching season on the coast of NSW. Minke whales, southern right whales, and large numbers of humpbacks migrate north from the cold waters of the Antarctic to mate and give birth in warmer subtropical or even tropical waters.

Can be seen along coast

During their trip along the east coast of Australia, they can be spotted from headlands and lookout posts, and occasionally even enter the larger bays and inlets. (A few years ago, a humpback frolicked in Sydney harbour and entertained ferry commuters for days on end.)

That much I knew, but so far, I had never seen any whale large or small myself, nor had I gone to any of the vantage points, although one called Cape Solander at the mouth of Botany Bay is less than a half-hour drive away from where we are.

But today, I resolve to stop dreaming and follow the urge. Since I wish to encounter the brutes at close range rather than through high-powered binoculars, who better to help me in this endeavor than Gonbei? (Well, in fact I can think of quite a number of better suited--read larger--vessels, but since none of these are owned by me, I make do with what I got.)

Likely whale-watching waters

On the sea chart, I have checked the approximate area where whales are reportedly often spotted from Cape Solander, and I have worked out that I need to venture only some three sea miles or so beyond the mouth of Port Hacking to be in likely whale-watching waters.

Port Hacking is a picturesque estuary south of Sydney,

near the inner end of which we now make our home.

<lynx alert: caption>

Port Hacking is a picturesque estuary south of Sydney,

near the inner end of which we now make our home.

<lynx alert: caption>

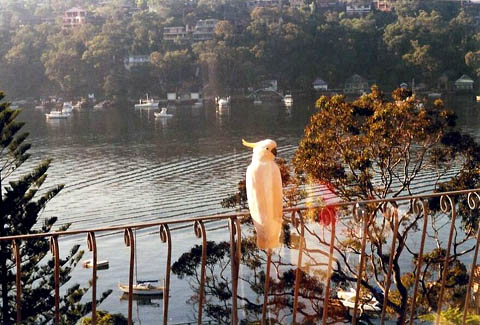

[Yowie Bay, through the window of our living room. Cockatoo a regular fixture.]

Photo by the author

</lynx alert>

Since there is a little matter of work to attend to in the morning, I finally set out from the pontoon in front of our abode shortly before one in the afternoon. By now I am fairly familiar with the little bays and inlets of Port Hacking, and I also have ventured into the open sea a couple of times on quiet days, but I never have been quite as far as where I'm headed today. And I certainly don't expect to bump into a whale right away, this trip is intended more to test the waters, so to speak. If conditions get rough, I will turn back immediately, is my inner resolve.

After about 30 minutes of swift planing, I am already in the wide crescent of Bate Bay at the mouth of Port Hacking, heading east. The waves are slightly higher here, but the swell from the Tasman Sea today is very moderate. I have put on my life jacket (inside the bay, I normally don't even bother), and the emergency lanyard that links my wrist to the kill switch on the motor (to prevent the boat from continuing on its merry way should I fall overboard) is tightly fastened.

No danger from cliffs

There is still not a single cloud in the sky. Progress now is slower, because I negotiate the waves rather than bouncing over them. The wind is in the northwest, which means that in case of engine trouble there is no danger of Gonbei being blown onto the imposing cliffs and craggy rocks of the outer coast. Rather, I would be slowly going outward (next stop: New Zealand). But actually the wind is light enough for this not to be a cause of great worry.

Even better: three out of five signal strength indicators on my mobile phone (snug in its waterproof pouch) are lit, reassuring me that I should still be able to reach the coast guard and call in the helicopters should my 9.8 horsepower Tohatsu (as old as Gonbei but also still in pretty good shape) unexpectedly give trouble.

Speaking of means of propulsion, I of course do have the oars fitted and ready, though it would certainly be a long hard pull back (and they are not terribly sturdy; I've already broken an oar once). I also carry the small square sail I made long ago, just as a backup (only of use if the wind direction is favorable, though). I haven't packed the bigger sail kit I made, because it sort of takes over the boat and is in the way when doing some serious motoring, such as now.

Keeping a good lookout

After about an hour more, I am pretty far out, roughly in the area that I had mapped out. Aside from a big ship or two on the horizon and the bright white sail of a large yacht far off, no other boats are around. The land is still clearly visible, but I am slowly drifting further away from it, because I have now turned off the motor. I can see far north and south along the coastline. As a good whaleman (did I tell you that I am currently reading "Moby Dick"?), I am keeping a good lookout while standing in the bow of the boat, steadying myself with the sturdy short mast.

But aside from a school of herring-sized fish breaking the surface at one point, the sea is untroubled and seems rather devoid of life. Another hour or so passes in musing and scanning the wavetops, while the sun is creeping closer to the rim of this immensely open and circular world. Since I believe myself capable of finding the way back, I intend to stay out until dusk today. But I do start up the motor and turn the bow around, slowly heading back towards where the sun will soon be setting (this is winter, remember).

No boat, no ordinary wave

Gradually I come to think that I may have gone too far, that the whales, if any, may actually be passing further in (after all, people do see them from the land), and sure enough, at around four in the afternoon, when I am back within about a mile from Cape Solander, the expected unexpected actually happens: startled out of a state of half trance I suddenly realize that for some time, in the direction of the shore, at a distance of maybe a hundred meters or so, I have been idly watching a foamy wave crest not unlike the wake from a fast moving boat. But there is no boat here and this is no ordinary wave!!

My heart makes a giant leap and a shout escapes from my lips (stupid thing to do, because whales possess acute facilities of hearing and startle easily). This is it! This is really a whale, no, two of them! I now see their black backs moving through the water at considerable speed, and some bubbly water rising around them, not so much like a spout, more like a misty shower. In accordance to schedule, they seem to be headed due north.

More mass hidden below?

Their size is hard to tell. The exposed part briefly visible to me is at least two or three meters long and I can sort of feel that more mass is hidden below, but I don't really get a good look, and there are no flukes that I can see.

I now make the second mistake in trying to head towards them, but they have already swiftly and smoothly dived, and I do not see them again. I try to estimate their path and hurry Gonbei in the direction where I think they may surface again, but in vain. Yet the sheer excitement and joy lingers on, as the reality of this encounter sinks in.

Yacht heading this way

In the meantime, the yacht whose lone sail I had been seeing far off has tacked a few times and is coming closer. After a while, it becomes clear that she is heading my way, and I also wish to speak her, if only to share the giddy joy that I am still feeling.

When we are within hailing distance, the yachtsman asks whether I am in trouble (Gonbei often elicits this kind of concern when frolicking in the wild blue yonder) and I reassure him that I am here entirely by my own volition. He reports that he has seen a pod of five whales but was unable to get closer, and I tell him about the two I saw.

We then head in opposing directions, and just as I turn away, my roving eye suddenly catches a glimpse of a WALL briefly emerging from the sea. This time the whale is much closer, and its enormous side is gray, not black. But the sighting is extremely brief, and the presumed humpback vanishes from sight almost immediately. Again I head north trying to forecast its path, but nothing more pierces the waves.

Ever smoother sea

I continue to cruise the area while the sun well and duly sets. As I slowly glide over the ever smoother sea, there is still enough light to allow me one more jolt: within less than a kilometer from the darkening shoreline, I see my fourth whale. It seems to be the same species as the earlier two (possibly a smaller minke whale), and it again blows a showery mist of foam and then disappears.

By now, this short trip of only a few hours has far exceeded my expectations, and in the course of it, the sea has acquired a new quality that is hard to describe, encompassing and reassuring and forbidding at the same time. And it is about to teach me yet another lesson: don't rely on gadgetry and don't blithely assume you know where you are!

It is now almost completely dark, and I am on the outer fringes of Bate Bay (or so I think), only a short way from the entrance to Port Hacking. While coming out, I have stored a waypoint in my portable GPS, and I intend to use that now to guide me on my way back in. I hit the "Go To" button, and the backlit display shows a little arrow that points, as expected, westwards, homewards.

Homeward bound

I can see the lights of Cronulla, a suburb that lies at the right side of the entrance to Port Hacking when coming in from the sea. To the left side, there should be Bundeena, a small village much beloved by artists and the PandA list's erstwhile resident philosopher Andreas Braem, located in the Royal National Park.

As I steer Gonbei in the direction suggested by the GPS arrow, which should lead me straight into Port Hacking, there is only one disconcerting aspect: I can see no lights whatsoever emanating from where Bundeena should be.

For a brief moment, I contemplate the possibility of a power blackout there (possible, but highly unlikely, after all, this is not California), while I turn the throttle of the outboard down, just in case.

And not a minute too soon. Suddenly I hear the unmistakable sound of surf breaking, and I see a white line looming straight ahead of me. Knowing that for ships small or large, breaking surf and a rocky coastline are usually much more dangerous than the vast open expanse of the sea, a cold fear grips me and hurriedly, I execute a 180-degree turn and head straight out again, while the GPS arrow is still vainly trying to pull me that way!

After going seaward for a brief spell, I clearly realize my mistake: earlier on, with the motor turned off, I had drifted south much further than I had thought. While believing myself still close to the northern end of Bate Bay, I was in fact already way past the entrance of Port Hacking and had almost run smack onto Jibbon Bomborra, a shallow rock formation jutting out from the bottom of the sea a short way offshore.

Bay behind headland

The GPS was luring me that way because behind the headland, there was indeed the bay where I had earlier stored the waypoint, but the way to get in there from the sea was not by a straight line but rather by giving the headland a wide berth. The only tipoff had been the lack of lights from Bundeena (obscured by said headland).

After this monumental discovery, it is a fairly easy matter to back up north a bit, until I can indeed see the lights of Bundeena, and then simply head into Port Hacking with its lighted buoys marking the channel.

The rest of the journey, over the dark glassy waters inside the bay, is uneventful, and shortly before 7 p.m., I am back at "our" pontoon (it actually belongs to the landlord, but we get to use it), where I pull Gonbei onto its grassy spot below the waterfront house, unpack my gear, and climb up to the second storey to tell Reiko and Sara and Akio of the wonders of the whale.

Whale tales (coda)

The above happened on Monday, 25 June 2001. A few days later, the newspaper reported that a humpback got injured (fortunately not fatally) by the propeller of a larger boat in Sydney harbour. Today was another golden sunny warm day, and I briefly vacated my desk and drove the car to Cape Solander for the first time. The sea was even more quiet than the other day and conditions for whale watching from this spot with its sweeping sea vistas were perfect (no haze or whitecaps to distract from seeing any spouts).

Would-be whale watchers were out in force, but during the almost two hours I spent there, no cetacean was forthcoming. Still, just taking in the view and the birds was also great. A pelican flew lumberingly by, and two sea eagles were gracefully circling far overhead.

A few days later, having read that the peak of this year's whale migration is expected to be over in a week or so, I went once more to Cape Solander by car (unfortunately no time for an extended boat trip). Reiko and Akio responded to my passionate invocations and tagged along, while daughter Sara chose to remain glued to the TFT screen surfing the net.

The three of us arrived at the cliffs around two o'clock in the afternoon, where we joined not exactly a huge crowd (this is not Japan after all) but--this being another fine-weathered Sunday--a good sized number of people with similar intentions, who informed us that there had already been numerous sightings today.

And sure enough: almost immediately after we had walked just a few paces from the car to sit on a rocky promontory, we saw the first spouts! Even with our economy-size binoculars, we could clearly make out the backs of two, three, four humpback whales that were playing on the surface for quite a while, not exactly close to shore, but not too far off either (less than a kilometer).

We excitedly pointed out to each other our discoveries and swapped binoculars (only two among the three of us). We soon found out that it is best to scan the sea with the naked eye, and then, when some action in the water manifests itself, focus on it with the glass.

That way we saw whales, with brief interruptions, almost constantly, maybe fifteen animals in all. Sometimes only the spout and a dark piece of back was visible, but once a large specimen splashed half out of the water, and several times we could clearly see the raised flukes just before a dive. Ah, bliss.

I know I'm boring most of you to tears and making a select few green with envy, so this will the very last missive you receive from the bow of the Pequonbei.

Went out once more on the inflatable three days ago. Waves somewhat higher than the other day, sky a bit confused. While churning outward, a big water police catamaran coming in from the sea spots me, ponders briefly, and comes alongside.

Have to show safety equipment: Life jackets? Check. Flares? Check. Marine radio? Check. V sheet? Um, come again? Large orange sheet with black V sign on it to indicate distress situation. Sorry officer, currently not carried on this vessel. A'right, but get one for next time. Where ya goin'? Whale watching? Know about the 100-meter rule? Sure do, officer. (Motor boats are not allowed to approach whales closer than 100 meters; people on surfboards and in the water may go as close as 30 meters. I should be so lucky.)

Inspection complete, the police cat heads in, I head out. But not all the way to Cape Solander, only a bit outside Port Hacking. Sea looks empty, no birds to be spotted either. (I've learned that they often indicate presence of whales.) Sky getting progressively darker (forecast was fine), better turn round. Barometer on wrist watch also dropping, but not alarmingly so. Get rained on rather suddenly and put oilies on too late. But it clears up in no time, and I decide to go for another spin. A bit beyond Jibbon Bomborra, yay! I spot a spout, and carefully close in. (Yes, of course I will observe the 100-meter rule.)

This time I am lucky: Gonbei's course ends up nearly in parallel with two humpback whales swimming in an eminently powerful, graceful motion on the surface. Spray partly enveloping the blueish gray bodies, but flukes clearly visible, pushing a strong stroke. For a while, I have the ideal vantage, then they get ahead and vanish.

I am content and turn to port. Get rained on some more, now swathed in foul-weather gear. Visibility greatly diminishes and the sea, pounded by rain grape shot, changes color to a whitish steely gray. Glance around apprehensively, relieved that wind and waves seem not really in a menacing mood. But once again, the realization how quickly conditions can change is driven home. Soon the sun is out again. Revel some more in the scenery of Port Hacking and the warm glow of another encounter.

Wolfgang Bechstein was born in Germany but says he has always felt more comfortable observing his country from the outside. While roaming the world in his youth, he briefly set foot in Japan, worked as a movie extra, and became fascinated by the local lingo. After studying linguistics and Japanese at Tübingen university, he came back to Japan in earnest in 1974 to work for a publishing company. He earned a B.A. in Japanese linguistics from ICU in Tokyo. Turning a passion for audio into a profession, he started working as a freelance translator in 1981. He established his own company, Prisma, in 1988, and translates mainly from Japanese into English and German, specializing in electronics and computers. He and his family relocated to Yowie Bay, New South Wales, in March 2001. Although he has applied for membership in the cafe latte society of Sydney, just between you and me, what he really came for are the waters.

- by Wolfgang Bechstein: Other salt-water adventures

- "Rigmarole"

- "Lights across the bay"

- "There was chirping too"

- "Sail ho"